In 1997, I read the book Bank Heist: How Our Financial Giants are Costing you Money, by the late Walter Stewart. I had just finished reading the 1958 book, The Legalized Crime of Banking, by Silas Walter Adams, yet the appropriately understated Canadian work caught my eye. It was worth the $30, as this book provided the missing piece to a complicated puzzle here at home. If you can't find a pdf version of this, check out Goodreads. Adam's work is available on archive.org.

In chapter 7 of Bank Heist, 'The Gnomes of Basel Unleash the Banks,' Stewart explains how the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) gave unprecedented power (and wealth generating potential) to the commercial banks by modifying the reserve system. This was the first time I grasped the nuances of the BIS (Basel Accord) reserve changes; or, at least, the implications of these changes. 'Only three of the member nations were stupid enough to go along,' Stewart writes, on page 115, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and, wouldn't you know it, Canada.

Since then, most other major economies have also 'gone along,' and it is increasingly difficult to believe that those who authorized the adoption of these policies – which enrich the banks at the expense of everyday people – were simply unwitting dupes. People know the banks are making inordinate profits at their expense, despite the disarming language that appears on their websites, they just don't understand how. The Bank of Canada would have us think:

'We use this ability carefully to fulfill our mandate of promoting Canada’s economic and financial welfare.'

The 'ability' described here is the payment of interest on 'settlement balances (or reserves)'. . . 'a unique type of money that the central bank creates.' This move, in the nineties, will seem almost reasonable, if we are to read the bankers' rationale; however, section 21 of the original 1934 Bank Act, and Section 23 of the 1985 amended Act, under 'Prohibited business,' state:

‘The Bank shall not ... pay interest on any moneys deposited with the Bank.’

That sounds pretty straightforward, but the mechanism remains obscure, and is understood by virtually no one; including, I am certain, all but one in a hundred bank branch managers. So the 'robbery' has been carried out for years, simply because the inner workings of our monetary system is a mystery, hidden in plain site. Banking has always been a deceptive practice of course – Silus Adams makes that point clearly – but twenty five years after the development Walter Stewart describes (in the wake of interest rate hikes that were not supposed to happen in this modified system), we are feeling the impact of the bank's self-serving policy more acutely than ever.

Suffice it to say, the Bank Act once prohibited the payment of interest on reserves for good reason. I must leave a more detailed explanation of this for later, instead, I'd like to show you – graphically, and in the Bank of Canada's own words – the most recent phase of this great bank heist. And believe me, this is very definitely 'costing you money.'

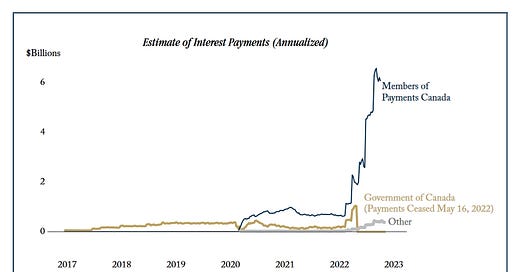

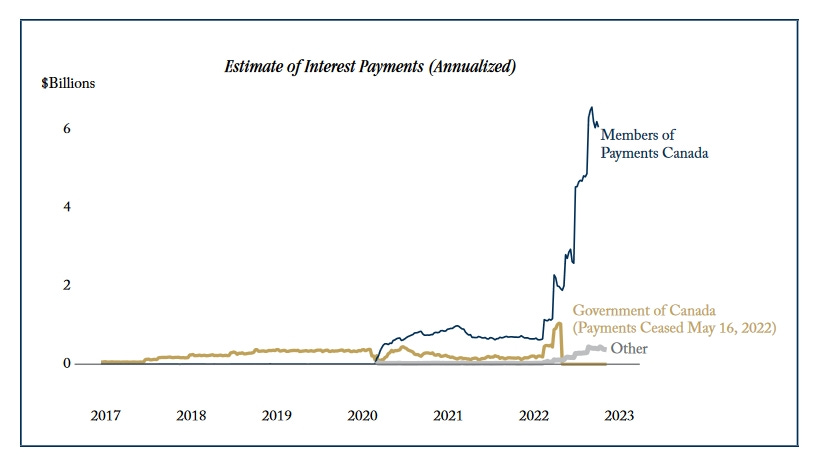

When the BoC was paying interest to commercial banks and interest rates were low, few would even have cared about the .25% (even if they had known about it). Some people knew, and spoke out; I'll refer you to the section in a 2019 article by Adam Smith of Toronto, explaining 'un-neutralized monetary financing.' Clearly, not enough people were outraged by the thought of interest on reserves, and now the bankers add insult to injury. With interest rates much higher, the amount being paid to banks on their reserves (4.75% at present, since the June 7th increase) is staggering. Here are the estimated costs (or rather, lost earnings):

As of May 2022, the government (which is, or should be, the people) was earning an annualized $1 billion on these reserves, while the commercial banks (and other members of Payments Canada) were earning approximately $2 billion. Then, as you see above, payments to the government stopped, yet the payments to commercial banks continues on up to $6 billion (risk free earnings on their reserves). The rationale provided (I quote here from the CD Howe paper 'Tombe, Chen - BoC Losses are Just Getting Started. What to Do?' ):

'For perspective, if the peak target rate is 5 percent rather than the 4.5 percent assumed here, then cumulative losses rise from $5.7 billion to $7 billion over the next three years. Importantly, the decision to cease interest payments on Government of Canada deposits as of May 2022 was significant. We estimate losses would otherwise be approximately $13 billion by 2025.'

In an earlier email update I mentioned the September 2022 Toronto Star column by Heather Scoffield: 'The Bank of Canada, for the first time in history, is losing money. Is that a problem?

I quoted, from this piece, a rationale from University of Calgary professor, Trevor Tombe:

'[T]he central bank’s finances would be a lot worse if not for a change made in May, by which the Bank of Canada no longer has to pay any interest to the government of Canada for its holdings.'

Alarm bells are ringing!

So it's okay to continue paying the banks, but when things get tough, the people must tighten their belts. Quantitative Tightening (QT) doesn't apply to members of the Payments Canada club; rain or shine, it seems, they will get their 'pound of flesh.'

What does the bank of Canada have to say on this?

You might look up the 1996 'Payment Clearing and Settlement Act' (allowing for the payment of interest on bank reserves), or the 1997 'Act to Amend Certain Laws Relating to Financial Institutions' (allowing for the payment of interesting on government reserves), but it took me some time to find the following simple statement on the BoC site:

'Effective May 16, 2022, Government of Canada deposits ceased accruing interest.'

Buried in footnotes, with no explanation – (nothing too apparent that is) nothing to see here – the people get short-changed again. . . robbed, pick-pocketed, whatever you want to call it.

And where does the money to pay this interest come from anyway?

Concern expressed by the media (and elsewhere) always amounts to: will the taxpayer have to cough up more to cover the shortfall (as was decided in some countries, such as New Zealand)? The Truth is, the answer is there in plain site, as explained on the BoC site (and quoted above, in part):

'Settlement balances (or reserves) are a unique type of money that the central bank creates.' (My italics.)

Just as central banks 'create' the money for reserve balances, they create the money to pay the interest on them too; ex nihilo, 'out of thin air.' So the balance sheet talk, to a large extent, is a kind of theatre, setting the stage for the next phase: the ‘New Fiscal Age’ (as I mention below).

Financial pundits and politicians alike would call this kind of money creation 'inflationary,' if it were to benefit the people. They get hysterical when money is created this way for government (opposition governments that is); and fair enough, lots of money has been created and misallocated. When the central bank creates money to pay interest to the banks though, apparently, this is okay; you never hear a whisper of complaint. The government (or the people that is) are S.O.L., but if the banks' bottom line is in jeopardy, the accounting can get pretty creative, and no one will say a thing.

Bonds paying interest to the government must be moved off the central bank's books as soon as possible (Quantitative Tightening – QT); but these bonds are okay if they are owned by the banks, paying interest to the banks. Either way, these bonds represent debt; but debt that profits a bank is fine, while debt that benefits the people cannot be tolerated.

It's always puzzled me that those same financial pundits and politicians lose it when central banks create 'fiat' money to spend on people, but when commercial banks create their 'fiat' money for people, in the form of 'bank credit' (multiplied up or created out of thin air), and put it into the economy as loans at interest, this is great business (and couldn't possibly cause inflation). Now we've just added a whole new wrinkle to this ages old mystery, but I do still believe this is the missing piece to the puzzle.

The solution to the problem, I have always maintained: if not full-reserve banks, then public banks.

Money is 'public equity,' and banks should be public utilities, not 'for-profit' business. Banks are (or should be) 'financial intermediaries' only; that's it, they should not be creating our money.

If a bank is not satisfied being a financial intermediary, and wants to earn the kind of profit commercial banks make today, then it should be classified as an investment bank, not a high street bank. Glass-Steagall, or something very like it, should be reintroduced as soon as possible. And if a bank is 'Too Big to Fail,' as I recall even some bankers saying, it is simply ‘Too Big.’ Period.

My favourite analogy from Catherine Austin Fitts (that I have also shared many times), compares the economy today with a game of Monopoly in which the banker is one of the players; the first time around the board, the banker can by everything (which is why the bank's money is kept separate). In the real world, bankers do get to play with this money, and they get away with it because they don't buy everything first time around the board (metaphorically speaking); that would be too obvious. Over time though, almost invisibly, all assets move into the possession of those with control over the money. That's the phase we are entering now, the 'New Fiscal Age' (the reason the WEF has said 'by 2030 you will own nothing. . .'), but this is a story for another time.

Perhaps I can close this with a conclusion, of sorts, from the above mentioned CD Howe paper:

'[F]inancial losses at the Bank will negatively affect government finances, likely causing adverse political and public attention.'

I do hope so. The reason we're in this mess is that the public paid no attention in the past. The only way out is to let our politicians know they can no longer be complicit in this heist, and that we want to start rolling back all of these polices - back to the 1984 version of the Bank Act, at least, if not 1934 (the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, and the ‘Four Pillars’), I would suggest.

I've included a number of links below for more in-depth reading. I do want to go back and revisit some of the earlier pieces, to dig further into the intrigue, confusion and controversy surrounding BlackRock, and those 'contradictory' statements from Larry Fink (and two past Governors of the Bank of Canada) mentioned in my first Substack article.

Thank you,

David

https://www.cdhowe.org/intelligence-memos/tombe-chen-boc-losses-are-just-getting-started-what-do

https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/spring/summer-2019/interest-reserves-history-rationale-complications-risks#history-and-rationale

https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2022/06/understanding-quantitative-easing/

https://www.frbsf.org/education/publications/doctor-econ/2013/march/federal-reserve-interest-balances-reserves/

https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/B-2/FullText.html