Neoliberalism

Part I: Kulturkampf, and the birth of the Uniparty.

The history of the world is the history of money; it is equally, and more obviously, the history of economic systems.

Capitalism and Communism; market economies and planned economies; traditional economies and mixed economies, and all the schools of economic thought they embody.

'Environments are invisible,' wrote Marshall McLuhan in his The Medium is the Massage. So too are the mechanisms (and machinations) of administration; hidden from view behind the 'masks and silence of the administered society,' as Herbert Marcuse wrote in his One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society.

This is by design, I would suggest. How many, after all, can define postmodernism? Yet this is our culture; the world – and environment – in which we live. I once took a random survey of some forty-plus people at my local coffee shop, and only one student came close to providing a meaningful definition. Most, if they had an answer at all (and the majority didn't) replied: “art” or “architecture.” Neither of these represent an answer of course. These things are merely expressions of postmodern ideas (at a particular point in time) and they do not constitute understanding; but this, of course, is that 'One-Dimensional' view of the world Marcuse wrote about. It is the reason advertising and propaganda is as effective today, as it ever was.

Postmodernism is the culture of globalism:

‘an economic system that obliterates national and psychological borders, undermines social bonds, and fragments the individual psyche, all in the name of turning active citizens into passive consumers.’

This is the best definition of postmodernism I've yet to see, in Eleanor Heartney's book on the subject: POSTMODERNISM. Postmodern culture maintains that we have no unique identity, that we are merely products of the consumer society. The main product of postmodernism is consumers, and we 'consumers' define our identity through the products we consume; critics of postmodernism assert.

Neoliberalism is the political-economic system for managing these passive consumers. It is a system that appears to work on behalf of consumers, while it continually (and invisibly) undermines every aspect of their existence. Like postmodernism, neoliberalism is a nihilistic ideology; it destroys real value, just as postmodernism destroys meaning.

Neoliberalism holds that every aspect of life should be subject to market forces. The entire world, and everything in the world, is viewed as a commodity, to be bought and sold in this market place. Everything of the earth is a natural resource, and every person on the earth is a human resource.

But how does the Uniparty emerge from this?

The one world economic system – globalism – needs a single, integrated political system, subordinate to market forces. This system is presented to us in different 'flavours,' because consumers like to feel they have a choice – we must feel we have a choice, also, to believe that we are free. Whatever the divisions, whatever political colour we chose, ultimately, we will be led to the same place in this system, because left and right are two sides of the same neoliberal coin. It is telling, perhaps, that in Canada, Liberals are red and Conservatives blue, while in the United States, the left is blue and the right is red. Right or left, red or blue; it makes no difference in the long run, and we must stop thinking in these terms.

Ronald Reagan told the world, before he became president:

“You and I are told we must choose between a left or right, but I suggest there is no such thing as a left or right. There is only an up or down. Up to man's age-old dream – the maximum of individual freedom consistent with order – or down to the ant heap of totalitarianism. Regardless of their sincerity, their humanitarian motives, those who would sacrifice freedom for security have embarked on this downward path.”

This, in a nutshell, is neoliberalism. Reagan's argument is convincing. What's not to agree with here? As we might expect though, there is another way of looking at this; another way to interpret 'up and down.' Subsequently (from the point in history at which the middle-class reached its zenith) 'up and down' relates more to the divide between rich and poor; or more to the point, the super wealthy, financial elite, and the rest of us – a beleaguered and much diminished middle-class, and a new, permanent, economic under-class. ‘Upward mobility’ is not what it once was, as generational expectations are now actively managed downward: “You will own nothing and be happy.” Even Friedrich Hayek, when he wrote his Road to Serfdom, could not have imagined that serfdom would arrive so quickly. It is highly unlikely, of course, any of us will ever become super wealthy, financial elites.

As George Carlin once stated: "It's a big club and you ain't in it."

As George W. Bush once told his friends: "What an impressive crowd: the haves, and the have-mores."

Although we are held out the promise, still, that if we play the game and succeed in this system, we may join their club. While most people don't aspire to be super wealthy, a sufficient number of us would support the idea that, in principal, we should all be free to become super wealthy – if we are clever enough or hard working enough (all those values of another bygone age). So we support the rights of individuals to be phenomenally wealthy, because we feel we should all have this right, and (perhaps) in the vain hope that we too can achieve this status.

But this is a clever design, I would suggest, by those who already have phenomenal wealth, to ensure their interest are protected.

If the bulk of our savings are moved into the stock market, as the banks encouraged from the 80s on, then we will be more likely to support policies that increase the price of our stock (in the system). Should we invest in Vanguard funds, for instance, we will support policies that make Vanguard more profitable for us. The holdings of such investment funds are lodged disproportionately in the portfolios of the super wealthy; but now their interests are our interests – at least, that's how it appears at a most superficial level. Meanwhile, the corrosive effects of maintaining such a powerful elite (in the excess to which it is accustomed) gradually obliterates the real interests of everyday people; as wealth, and thus power, concentrates in the hands of increasingly disassociated, 'have-mores' (who, it would seem, can never have enough).

For this same reason, while I generally support the ideals of Libertarians, because they are generally sound, a deeper, more nuanced understanding of economics and monetary issues is required, or the outcome is likely be precisely the opposite. Instead of that utopian future, in which wealth, autonomy and political freedom is maximized for all, we will end up with a form of totalitarianism – Inverted Totalitarianism, no less – and the 'serfdom' Hayek spoke of. The history of Libertarianism, incidentally, is deeply interwoven with that of neoliberalism. Libertarianism has changed over the years, having once sought, surprisingly, to abolish capitalism and private ownership. All things, in time, become their opposite. More on this in Part II.

In a similar sense, though less radical, the early neoliberals supported labour rights and sought to abolish monopoly capitalism. The post-World War II German Ordo Liberals, I would suggest, provide a workable model for our times, but I am getting ahead of myself here.

First, I must flesh-out a short history of neoliberalism.

As Noam Chomsky famously stated: "Neoliberalism is neither new, nor Liberal." It should not be surprising then that it was Republicans in the U.S. (under Reagan) and Conservative in the UK (under Margaret Thatcher) who introduced neoliberalism to the wider world.

Neoliberalism wasn't new, as Chomsky pointed out, it had already been 'tested' in the fascist 'Southern Cone' of South America, starting in the early seventies. Three countries with CIA installed fascist military governments (Argentina, Uruguay and, most notably, Chile, under Augusto Pinochet) would, almost immediately, implement the new economics. These Military governments brought in (or were told to bring in) economic advisers from the University of Chicago – 'Chicago Boys,' as they were known – to rebuild their economies according to neoliberal principals.

We could be excused for thinking this was a coup by the Chicago mob, the way anyone who spoke out was quickly 'disappeared' – tortured and / or murdered – but this global coup d'état, from the start, was more likely the work of the international banking cabal, or those behind the international banking cabal. As a study of the CIA's early history, from the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) days, would suggest.

The Chicago Boys and their backers hoped to introduce a new system, world wide, to replace the Keynesian economic model that had dominated since the end of the World War II. It wouldn't matter that this model wasn't successful in Latin America. These countries, for the most part, are still a mess (economically speaking); but all along, failures would be blamed on the ousted governments and their policies.

Should neoliberalism have been tainted by association with the brutal military juntas that first introduced it, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher washed all that away, and brought respectability to this new economic system. Before long, most of the world followed suit, and became neoliberal too. So complete was this coup, that even the left was compelled to get on board, under Bill Clinton in the U.S. and Tony Blair, in the UK.

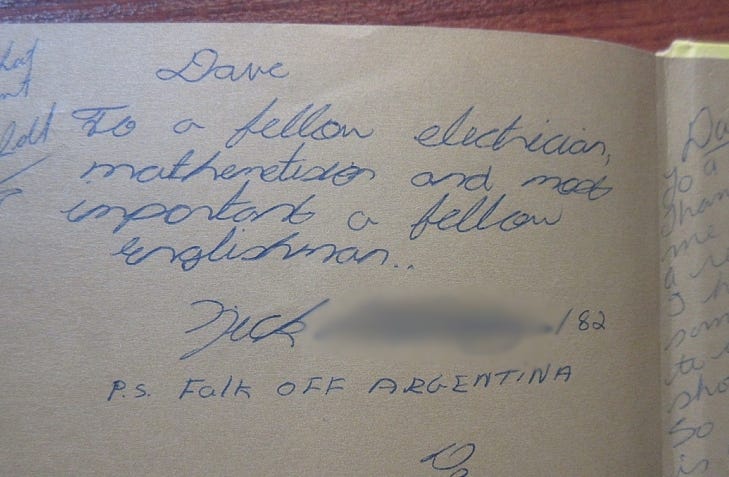

Part of neoliberalism's 'distancing from its past,' I would suggest, was the Falkland’s War. This conflict happened the year I left high school. One of my classmates, a fellow Brit, left the following inscription in my 1981/82 Year Book.

This pretty well sums up the media generated enthusiasm for any, and all, military misadventures. All wars are banker's wars, we must not forget, and the tactics (and subterfuge) employed, to realize geopolitical and economic goals, knows no bounds (once again, as we watch the news today, we must keep this important lesson in mind).

That the first leaders to adopt neoliberalism were fascist dictators, was a most inconvenient truth (to the proponents of this new economic model). So what better way to distance those whose role it was to 'popularize' the new economics, from those who first implemented it, than to stage a war between these key players? The theatre of life, on the world stage, really is the greatest show on earth.

Next time I will dig a little deeper into this geopolitical theatre, the political schizophrenia of the 90s, the fascinating (and equally tormented) ‘split-personality’ history of neoliberal thought. Why, for example, did Ludwig von Mises call Friedrich Hayek a “Keynesian”? It was Hayek's work that provided the basis for Milton Friedman's theories, which ultimately eclipsed Keynesian economics? Was the suicide of Henry Simons – the 'Chicago Plan' economist who called for an end to the Fractional-Reserve banking system – really a suicide?

The history of money is not only the history of the world; it is the most interesting story in the world.

Thank you for your continuing interest,

David