Be Released from the 'Bond' Age

Financialization didn't start with Neoliberalism

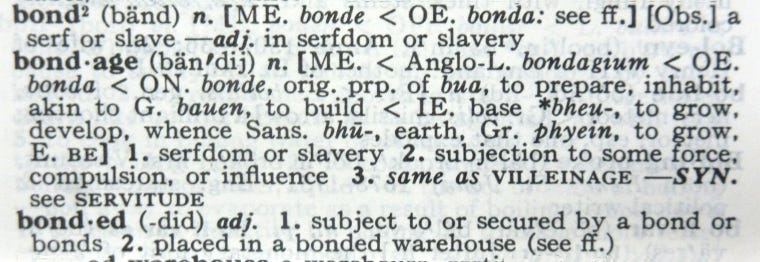

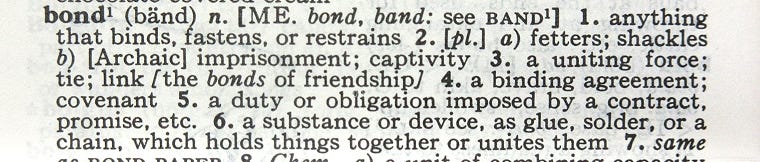

In this postmodern world, the meanings of words (as I've mentioned many times before) continue to shift. If you don't have an old dictionary, you might want to find one, and keep it on hand; because the debasement of our language, along with our currency (and culture), is bound to continue — for a while yet. An online search now will yield an entirely different interpretation of the word ‘bondage’ — you might even call it a ‘fetish’ given every reference to this now leads to a porn site. This from the sadomasochist psychopaths who run the world, of course, who are determined to teach you to love your bonds – just as they want you to ‘own nothing and be happy.’

And even now, when more and more people understand the power elite's plan for a new technofeudal world, we will be powerless to do anything about it, because the nature of money (and thus power) is not understood.

Not only is there an almost total lack of knowledge about how our monetary system currently works (please revisit my earlier ‘Bank Heist’ post) or even how it worked historically (Making Money: Coin, Currency and the Coming of Capitalism), a dangerous misunderstanding has been fostered — intentionally, it would seem. I would even go so for as to call this real ‘malinformation’ — a new term that we hear on occasion (which definitely won't be in your our old Webster's Dictionary). As a result, the actions we take (in the hope of fixing our economy) are likely to have precisely the opposite effect. This is the inevitable — and anticipated — final stage of that Great Reset transition, however things unfold.

Whether the system collapses of its own accord (as Ponzi Schemes do), or is intentionally collapsed at an opportune moment (as those bankers have often done) — or is unintentionally collapsed, the result of actions taken by well-meaning yet uncomprehending politicians — the results will be (essentially) the same: a massive contraction of the money supply and an equally massive transfer of assets from those without money to those with money.

Again, in any of the above situations, those with money (or a grasp of these concepts at least) will win. In an inflationary scenario, those with cash on hand will likely buy assets (these may or may not appreciate in value, depending, but that's another story). In a deflation (as in the depression, where the Fed reduced the money supply by 33%) every dollar held actually gained purchasing power. Spuriously attributed to Thomas Jefferson:

“If the American people ever allow private banks to control the issue of their currency, first by inflation, then by deflation, the banks and corporations that will grow up around them will deprive the people of all property until their children wake up homeless on the continent their Fathers conquered. . .”

You can read more about this on the Monticello website, but I share these words because (like so many of those quotations floating around the monetary universe), ‘spurious’ or not, this analogy perfectly describes the reality of our current situation:

First expand the money supply and encourage debt; then contract the money supply, and strip those who cannot find a chair (when that proverbial music stops) of their assets. The game is elegant in its simplicity, and diabolical in design. No surprise of course, these characters have been at it for thousands of years — since Jesus got pissed off and kicked those moneylenders out of the temple. All these years later we are really no wiser (it would seem). The moneylenders / money creators must belly laugh over their cigars every time they pull this off, and here we are again. That old ‘capital adequacy’ (0% reserve) system (introduced 1991-1994) is no longer ‘adequate’ (the capital is no longer adequate that is) because who knows the real value of anything anymore, starting with the dollar?

A new system is coming in (must come in), whether we like it or not. We hear conservatives everywhere today, repeat the same solutions to this problem: “balance the budget and pay off the debt.” This wasn't an option, even in the old fractional reserve system, because Ponzi Schemes, as a friend at the Isle of Man Treasury once told me, “eventually hit the wall.”

Calling out this fact is undoubtedly going to ruffle a few feathers, since balancing budgets, and paying off debts (in most situations) isn't a bad idea — and most conscientious people will see this is a prudent idea. But the system is not designed this way. In a debt-based money system, the money is debt. More precisely, the money is backed by debt — mostly bonds and other government securities. If all the debt were to be paid off, there would be no money in circulation. Further to this, deficits are new money coming into circulation (or they should be). Too much money has been created, misallocated and/or misappropriated. There is certainly wasteful spending, and bloated bureaucracies too, all of which should be cut, but these are a separate issues. For now we must stay focused on the nature of our monetary system.

As our friend, the 21st Century Adam Smith always says: the economy is like a car with no brakes. You can accelerate and change direction a little — but there's no slowing down, and there's no stopping (in this analogy too) until you hit a wall (or steer into the guardrail). Kate Raworth, in her Doughnut Economics: 7 Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, uses the analogy of an aircraft that has taken off, but has no plan to land: ‘locked on autopilot, expecting to cruise at around 3% growth forever.’ If that 3% can’t be maintained, we have a problem; and we have a problem anyway, as eventually the dead weight of all this accumulating debt makes it impossible to maintain altitude.

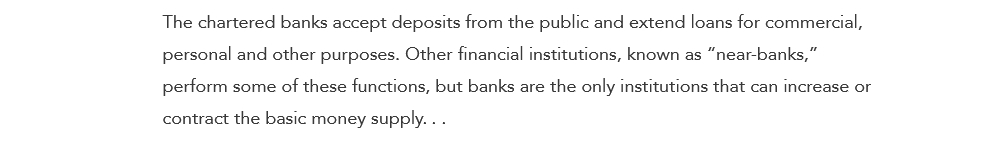

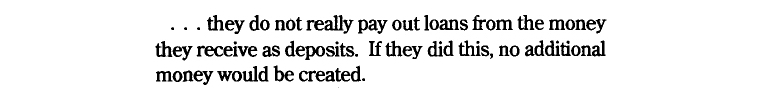

Until 2020, most of the money circulated was created by commercial banks, in the form of loans. I’ve shared the graphic below before, from the Bank of Canada.

If you check The Canadian Encyclopedia’s page on banking, the first paragraph (and the first line here) will give you the impression that banks lend out deposits, however:

From the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Modern Money Mechanics Publication:

The commercial banks too create money ‘out of thin air,’ just like central banks, but central banks always get the blame when there’s too much money sloshing around in the economy and inflation becomes a concern. The trend of commercial bank created money accelerated (encouraged by falling interest rates) from the 2008 Great Financial Crisis until 2020, when ‘emergency’ money created by central banks flooded the world's economies. Since interest rates have risen (although this was coming anyway), commercial bank money can no longer be created in sufficient amounts to keep the bubble inflated, so central banks must continue their money creation. I explained this in more detail in my Monetary Machinations Substack. To see a graphic representation of this, please revisit the above page (scroll to bottom).

We are in a ‘debt trap’ of course. It can play out in various ways, and be extended to some degree, but there isn’t an easy way out of this. The government's preference will (as always) be an attempt to inflate the debt away. Hence, those recent, token, interest rate reductions; but we're talking about unprecedented amounts of debt now, and an alternative plan is required. This is why central banks and governments have been talking about Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). I’ve written a lot about this already (if you want to check some of my earlier Substack posts).

It’s going to be difficult to clear balance sheets of the massive amounts of money that have already been created. Assets have been inflated in price, but the money used to purchase them doesn’t actually exist now. This is what the financialisation of our economy had done, and a major revaluation will likely be required. So there is a way forward, which will seem unpalatable to some, but no more unpalatable (I'm sure) than the alternatives being put forward by those BIS and WEF authoritarians, who lust for absolute control over your life.

We must take a trip back into history now, to see how this system evolved. If you feel your eyelids getting heavy at this point, and your mind is suddenly drifting off, you've probably been conditioned to respond this way. It’s the reason monetary reformers everywhere have so much trouble communicating these ideas. One day I must write a piece on this phenomena. Sometimes is almost seems like a kind of black magic, and if you read the history of those old banking families, that actually wouldn’t be surprising. For now, suffice it to say, the powers that be would rather you didn’t think about this subject at all. So grab another cup of coffee, and stay with me :-)

‘Bonded Labour.’ Feudal serfs and their ‘tax farmer’ in the fields — What’s old is new again, and I like the hoodie. Just for laughs, here’s a look at an alternative model, the anarcho-syndicalist commune — Monty Python.

Coins, of course, date back thousands of years, to the silver “Shekel of the Sanctuary” and beyond. This ‘commodity’ money was originally a material with inherent value, and its form has hardly changed in 3000 years. But we must skip over this interesting early history, to the second millennia, with its tally sticks, and the first bonds. Bonds, in fact, replaced the ‘stock’ and ‘stub’ (foil) ‘tally stick’ system that has been used (successfully) since they were introduced by King Henry I in the 1100s. This system (of wooden sticks with notches cut in them, split down the middle) was so effective it functioned right up until 1826. Tallies were largely supplanted though, during the reign of Charles I and Charles II in the mid-1600s, with the introduction of bonds, which, soon thereafter, led to paper money. Perhaps the most interesting point here is the transition from private money (with coin), to public money with tally sticks (created by the crown), to bonds (which represented private money borrowed by the crown). Coins were not debt, tally sticks were not debt — one was a commodity, the other represented a commodity — but bonds were debt.

To quote from Christine Desans' Making Money: Coin, Currency and the Coming of Capitalism (pg 235):

‘[R]efracted through the new and oddly narrowing lens of liberalism, coin looked more like commodity, pure and private, than it ever had before. As to tallies, their demise generated the conditions for a new kind of circulating credit: government bonds traveled hand to hand as had the older tallies but [they] bore interest from the beginning and operated to borrow money instead of compensating people for illiquid resources and services.’

She continues:

‘Bonds offered unprecedented opportunity to reach a large pool of popular lenders. The Change would make investors out of a broad swath of citizenry for the first time. Bonds also furnished the English with a new kind of liquidity: circulating credit that the government paid individuals to hold.’

It is true that the private Bank of England was founded on a subscription model (an original £1.2 million pounds in gold) paying 8% to the first 1268 investors, but bonds would allow for much greater participation in this process. The important thing here is that banking, at this stage, was more about attracting already existing ‘wealth’ (usually in the form on gold and silver) from ‘investors.’ Gold and silver, as commodities, did not pay interest; but now, as ‘money stock’ (backing for the new paper money) they could. The same could be said for tally sticks, which in the end were absorbed and phased out (in part) as a component of the initial funding of the Bank of England.

Without getting too far into the details of this evolution, tallies, in effect, became ‘Tallyes of loan,’ which were ultimately replaced by ‘Treasury Orders,’ and these early ‘bonds’ circulated as a kind of paper money. They were not quite money, because they could not be cashed on demand, but these ‘private bonds’ led to ‘Promises to Pay’ a ‘fiduciary instrument’ that really was paper money (and even, in the original form, paid interest dividends).

This paper money became separated from the underlying bond however, to circulate (publicly) while the bond still represented a private contractual agreement, paying interest to its owner. Tax revenue made possible by economic activity stimulated by new money in circulation (in one form or another) guaranteed interest on the bonds.

Anyone reading this far will likely know the introduction of income tax in the United States, through the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, made the private, for-profit Federal Reserve (founded that same year) a viable business venture. The ability of the government to levy taxes in this manner (and on a permanent basis) is what made it possible to pay the 6% dividend on shares in the Fed (to this day), held by its member banks. These shares (which you and I cannot own) represent the capitalization, ‘the stock’ – the ‘base money’ — upon which this enterprise is based. The Fed (in the U.S. at least) is why taxes, which were not needed before, now can never go away. It is also the reason the debt is as large as it is, in the U.S., and almost everywhere else in the world.

So how do we turn this around?

Some might say ‘nationalize the banks’ and ‘monetize the debt.’

This has been done in various places, with central banks too. The Bank of England, was nationalized in 1946 and the Bank of Canada in 1938. Did this help. We'll yes, arguably, for a time. Central Banks shouldn't be privately owned, but if the public doesn't understand the basics of how the system works, these banks are still likely to work against the peoples’ interests (public or private), led by the private Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the private Federal Reserve.

When you hear someone say, usually with a note of disapproval, they're going to monetize the debt; you might reply, the debt is already monetized. That's what our money is: debt. What they mean by this though, is that instead of banks purchasing and holding the interest-paying debt (in the form government bonds and securities), these will be held by the central bank. I explained some of these technicalities already: Monetary Machinations.

What politicians need to know (if they plan to do the right thing) is that there will be immediate repercussions for trying to do two things that are effectively impossible to do. Even cutting the ‘deadwood’ in government bureaucracy will yield apparent savings at first, but the wages that are cut, represents money that now isn’t circulating in the economy. Of course, those who are dismissed from their government jobs will not be happy with the administration that does this. Others will be effected though as their business slows, in time, because of fewer dollars circulating. These people might feel the government is on the right course (and it would be), but if things get tougher, the government in power will take the blame. . . DOGE Days Trailer:

“There’s a whole forest of deadwood out there, we’ve gotta get chopping, buddy!”

No politician can fix this problem without systemic change — without real monetary reform. The Ponzi Scheme is too far along and the only real question now is: can the old system be unwound without a collapse? Politicians don't understand the current system at all (apparently), and they certainly don't have the knowledge to design a replacement. So again, this falls to the people, because politicians will, for obvious reasons, let their banker friends design the new system; and you don't have to be a genius to guess who will benefit from the system these folk come up with.

As I've said before, the monetary system is going to be reformed; if we don't demand a system that works for us, we’ll be given another system, that works for the bankers.

A great example of a now popular politician who doesn't understand the monetary system, is Javier Milei. First he was going to use the U.S. dollar, then he was going to use Bitcoin, then he invited in BlackRock (following through on the invitation extended in Davos). Every one of these monetary ‘plans’ serve only to undermine the sovereignty of the nation. He was going to cut, cut, cut. (“afuera, afuera, afuera”). This got him into power, and this is what he's been doing, but Milei’s earlier monetary plans (to have even suggested these options) shows he has little to no understanding of money mechanics. BlackRock, however, brings in capital that will mask the impact of his other policies (for a time), and make it seem as if he’s doing a great job; but the multinationals are there for one reason: to extract a profit.

In that speech to the WEF in Davos, Milei looked all bad ass and in command — telling those socialists off — but then pleaded for the WEF member multinationals to come to Argentina. This was all theatre of course, and the nation is now pretty much own by BlackRock (if it wasn't already). This isn't a victory, it is another neoliberal coup, in the place where neoliberalism was born (neoliberalism Part I); except that neoliberalism has morphed into something else now. Since the late 70s, early 80s, neoliberalism served elite well. As the money supply was expanded, and business activity artificially stimulated, real wealth was extracted by means of the offshore banking world — which also sprang up, in earnest, in the late 70s and early 80s. This isn't a coincidence; these Offshore Financial Centres (IFCs) are an essential component of the neoliberal scheme. But this is a separate story, to which I must return later.

The system BlackRock is bringing in now is technocracy — ‘techno-feudalism’ might be a more appropriate description. You've heard those WEF control-freaks talk about their vision of the future for so long now, and you've also heard Larry Fink describe how he sees it working. I've shared the Larry Fink link before. Capitalism is in the process of destroying itself (with its own capital), as Marx said it would.

So what do we do?

We can't pay off the debt (there isn't enough money in existence) and yet we must get rid of the debt. Now there's a conundrum. The debt shackles us, but also, a lot of people depend (directly or indirectly) on the interest from bonds. Anyone who owns bonds at the moment (and must now hold them to maturity to avoid selling at a discount) certainly doesn't want to see bonds defaulted on. We must return to this too.

The bond in itself isn't a problem, but a system built on bonds is; depending on who owns them, and what they do with them. Bonds denominated in other currencies can be a big problem (because of changes in the relative value of these currencies), bonds held by foreign countries too (because they ultimately extract wealth from economies). Unless you have the world reserve currency, like the U.S. (for the moment), you are subject bond vigilantes who can control nations by controlling their bonds (as Rothschild first cornered the British bond market after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815).

Syndicates of lenders organized as early as 1640, and still exist, buying, among other things, municipal debt; which now feels a little like getting a loan from the mob. Bonds held by banks are particularly problematic, as they facilitate the multiplying up of money, while they draw wealth out of the economy in two ways: as dividends collected on the underlying bond, then as interest received from loans issued. Recently a third way was added, when banks started to be paid interest on reserves at the central bank (again, I talked about this in Bank Heist).

Importantly, the interest extracted from loan payments becomes, in a sense, tangible; it becomes permanent (some use the expression ‘everlasting’ money). This is added to the bank's profit (and capital stock); while the loan itself (which was issued as ephemeral bank ‘fiat’ money) is written off the books as the loan is paid back. This ‘money’ actually disappears; money creation, money destruction. The end result of creating money ‘out of thin air’ is that, ultimately, all real value gradually accrues to the banks — in the form of interest, at the current rate of interest.

The banks (and those in the know) do not sit on cash, they convert it into hard assets, or purchase more bonds — upon which more ephemeral money can be ‘spirited’ into existence, just long enough to extract more real ‘sovereign’ money from the economy. As a result, at the end of the neoliberal period, we have asset bubbles in all areas, real estate especially, and not enough money in circulation for everyday people.

Clearly, I've only scratched the surface here, and I cannot present all of the possible solutions in one short, introductory post, but let me quote once more (for now) from Making Money. As Tallies diminished under Charles I, they ‘were quickly converted. . . into a liquid advance; they acted as a request or channel for a money loan rather than as a method of creating a non-interest-bearing public credit currency.’

I am not advocating a return of tally sticks of course, but I would suggest the return of non-interest-bearing public credit currency, and a system that could (hopefully) endure for centuries — to keep the moneylenders / money creators at bay. It was Henry I who began the dismantling of feudalism with his Charter of Liberties (forerunner of the Magna Carta), and a democratic money (as Christine Desan would call it) is essential if we are not to descend, nearly a thousand years later, into technocratic neofeudalism. How fitting that our new money should be inspired at least by that Great Plantagenet King (if not of the House of York, from the House of York) and his enduring ideas around the subject of money.

Henry I. 1100-1135. AR Penny (21mm, 1.39 g, 10h). Double Inscription type (BMC xi).

Now, as then, wealth is concentrated in (and controlled by) a small percentage of the population. These folk would be happy to lend their money at interest, and profit from our collective labour. In part, this is what those public-private partnerships are all about, but there's an easy solution to this. As monetary reformers everywhere have said, many times before, a monetarily sovereign nation does not need to borrow it's own money, and pay interest on this money, when it has the ability to create it's own money. This is pure folly.

There would still be a role for bonds of course, as they once existed — for specific projects — whereby investor's money could serve a productive purpose. They should not be used to enable a private currency (as in the giant public-private partnership that is our system now); benefiting a few, invisibly, at the expense of the many, and enriching the bankers beyond measure. The people who once pretended to be capitalists, misused capital, destroying capitalism in order to bring in a strange technocratic fusion of communism and fascism.

An honest, sound money is required, if capitalism and democracy are to survive. There are so many alternative models and variations on themes to explore, and now is the time for monetary reformers (who have essentially been talking to themselves for the past few decades) to be front and centre. If we are not actually part of the conversation, we’re going to get whatever crazy scheme the technocrats can dream up to keep us all in bondage.

I hope you've enjoyed this very brief the history of money, and I look forward to continuing this conversation. Thank you for your continuing interest, and support.

David

Thomas Greco has some excellent thoughts on the subject, some of which I've discussed in my own Stack. We're going to need to Buckminster Fuller this, imo. Much imagining from a new space needed.

https://suzanneokeeffe.substack.com/p/building-a-globalist-free-society

https://thomasgreco.substack.com/p/chapter-twelve-how-to-solve-the-money

You have so much insight into money, David. I learn so much from your substacks and chats. :)